Performance Work

Performance Work

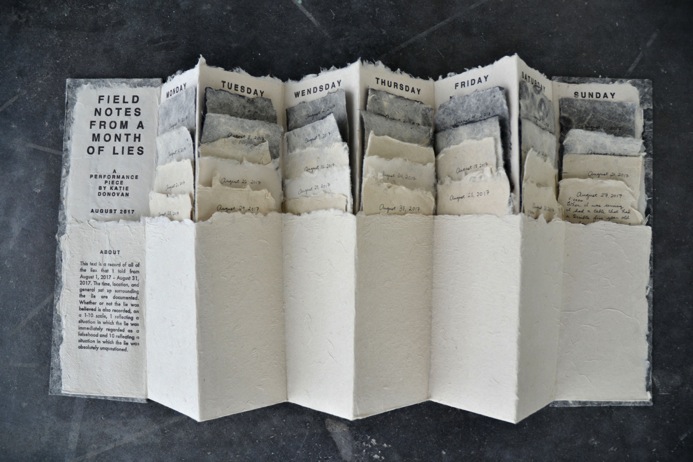

"FIELD NOTES FROM A MONTH OF LIES"

Performance Piece and book art

This book holds a slip for each day of August 2017. As a performance piece, I recorded every lie I told during this month. The lies were written on the slip with their appropriate date and I rated the degree to which I thought the lie was believed. The book that I made serves as a relic for the performance piece that only I was privy to in its entirety.

"Constructed memory game"

Performance Piece

Similar to "Drawing With Katie," this performance piece was also designed to be potentially reenacted multiple times. On December 6, 2016 this piece was performed in Southern Illinois University Edwardsville’s MUC, in the Dogwood Maple Room.

At the beginning of the performance participants are given a synopsis of the following introduction:

"Constructed Memory Game" is a performance piece that is largely influenced by an episode from Radiolab, a WNYC production, titled, "Memory and Forgetting." This episode interviews science writer Jonah Lehrer and Joe LeDoux. Most of the discussion from these interviews can be broken down into the following:

1. While we think of memory as a filing system in which memories, similar to master copies, are formed when an event occurs and are stored away until we reminisce on them later, this is largely false.

2. When we remember or reminisce on a memory we are not pulling a "master file" in its purity from our mind filing system, but rather engaging in a creative, constructive activity. The same parts of our minds that light up when we write a song or draw a picture light up when we remember or reminisce on a memory.

3. When we form a memory we form a neurological construct in our minds. Experiments have been done on lab mice to investigate how we form memories and how these memories function over time. Scientists would play a certain tone, then give a lab mouse, let's say Lab Mouse A, a very small shock (nothing inhumane, but enough so that when that tone was played it again, Lab Mouse A would tense just a little, expecting an unpleasant, but not harmful, shock). These researchers believed they had a drug that would erode the neurological construct (memory) being formed so they experimented with playing the tone for the mouse, giving it the small shock, and then immediately giving it the drug to erode the memory. After Lab Mouse A received the drug almost immediately after the shock its behavior towards the tone changed. When they played the tone for the mouse again, it would appear relaxed, as if it was not aware that another shock was coming. The memory of the tone-shock procedure had been wiped.

4. Researchers pushed this understanding with another lab mouse, we'll call him Lab Mouse B. Lab Mouse B was given the same introduction as Lab Mouse A: Scientists would play a certain tone, then give a Lab Mouse B a very small shock. However, after some time had passed, the researchers played the tone and immediately, as Lab Mouse B began to tense up in anticipation of the shock, gave him the drug without shocking him at all. When they played the tone for the mouse again, it would appear relaxed, as if it was not aware that another shock was coming. The memory of the tone-shock procedure had been wiped, this time without the shock. The memory was wiped while Lab Mouse B was anticipating the shock, or remembering that a shock was coming. This would indicate that memories are constructions that we create and can be altered at any point, not just when they are formed.

5. Researchers did further experiments, giving lab mice a series of tones. Lab mice would hear 2 tones, Tone A and Tone C and be shocked after each one, forming the memory that Tone A and Tone C result in a shock. After some time had passed, researchers would single out a certain tone, let's say Tone A, and make the lab mice forget Tone A by giving them the drug right after they heard it and without a following shock. The next time the mice would hear Tone A they would appear relaxed. But when Tone C was played the mice would tense up, indicating that they remembered that Tone C would result in a shock. Researchers were not giving the mice brain damage but truly isolating a memory and eroding it.

6. Researchers also believe that the more we reminisce on a memory or "replay" it in our minds, the further it is from the actual event that occurred. Part of this is attributed to knowledge and emotions that we acquire after the memory. Say I have a memory of playing chess with my uncle Paul when I was 5 years old. Paul won the game. When I was 8 years old, Paul was arrested for embezzlement. When I turn 10 years old and I reminisce on playing chess with Paul when I was 5 years old, I may color the memory some, based upon the arrest.

At this point, participants are given the following instructions for playing "Constructed Memory Game:"

1. Make sure that you write your name and email on the index cards provided.

2. For the next twenty minutes, everyone will close their eyes (except for me because I will be writing an objective account of our constructed memory, meaning simply what everyone says). We will all be verbally constructing a "memory" of what happened today during this performance piece. Each person may choose to add events/stages of the memory. These events can be entirely mythical, unrealistic, etc. but they must follow a linear order and start in this room, on this date, at this time. Please speak slowly so that the dictation process can be made easier, but also so that everyone can form a clear vision in their mind's eye of the events being described. Everyone will naturally add details in their own way. For example, if someone says, "My best friend Sasha walked into the room, threw the index cards on the ground and was upset," we would each have a very different idea of what Sasha looked like or how she expressed being upset. Visualizing what is being said is very important. The written account of what is said will naturally differ very much from your visualization.

3. I will let everyone know when we have 1 minute left.

4. I will use the index cards to email you a receipt by the end of the day, thanking you for participating in this performance. In 6 months I will email you again, requesting that you summarize, in at least 2-3 paragraphs, what you remember happening in our verbally constructed memory. In 1 year I will email you this summary that you provided me at the 6 month mark as well as the objective written dictation of our verbally constructed memory.

On December 6, 2017 I will publish the objective written account of the constructed memory created on December 6, 2016 in full. As I will only be emailing the participants the full account at the end of 2017 I will only publish a small excerpt of this written account here:

- "Mounds and mounds of white fluffy dandruff fill the room.

- The dandruff turns to snow.

- The snow melts into a pool and we all swim in it."

"Drawing with Katie"

Performance Piece

“Drawing With Katie” is a performance piece that was designed to be potentially reenacted multiple times. On November 29, 2016 this piece was performed in Southern Illinois University Edwardsville’s Art and Design building.

At the beginning of the performance, audience members were instructed with the following parameters:

-

The piece would be approximately 20 minutes long. The timekeeper for the 20 minute mark, Timekeeper A, would let the audience know when they had 2 minutes left.

-

Another timekeeper, Timekeeper B, would announce 2 minute intervals.

-

Katie would begin the performance approximately 15 feet away from a drawing that she had made with ink on paper, mounted to foam core and framed openly without glass.

-

Once Timekeeper A would announce that the 20 minutes had begun, Katie would cross the room and approach her drawing with a box cutter in her left hand and the same ink pen that she used to render the drawing in her right hand.

-

Once she would reach the drawing, Katie would count to 10. Once she reached 10, the audience had the option of watching her cut the drawing with the box cutter or audience members could come and take Katie’s right hand with the ink pen in it, and draw for her.

-

Each audience member could potentially draw for Katie by moving her hand, but only for 2 minutes at a time. Once their 2 minute time frame was up, Katie would announce, “Time,”and count to 10 again. Once she reached 10 she would either begin cutting or another audience member could chose to use her hand to draw.

-

Audience members could choose to draw twice, but not twice in a row.

-

If Katie began to cut the piece, audience members could still intervene and take her hand to make her begin drawing.

-

Audience members who would chose to draw with Katie’s hand must keep her right hand moving throughout their entire 2 minute time slot.

-

If Timekeeper A announced the final time, but an audience member was only 1 minute into their allotted two minutes to draw, that audience member would be allowed to draw for another minute.

-

Audience members and Katie would be allowed to discuss the unfolding performance. Audience members would be allowed to ask questions during the piece.

During the November 29, 2016 performance, the drawing was only cut once. Approximately six audience members chose to draw by moving the artist’s hand. Two participants drew twice. The piece lastly approximately 20 minutes and 30 seconds. The audience and the artist discussed the concepts and intentions behind the piece during most of the performance.

"Fountain" or "my cup runneth over"

Performance Piece

The parameters of this performance require the performer to remain under the tap of a water dispenser, with their mouth open until the very last drops of water pour out. Swallowing as the water poured out would be dangerous and likely cause choking, but allowing the water to spill outside the mouth as it came out would still allow the performer to breathe. This enactment took place over the course of 23 minutes.